昨天出席了兩場開題答辯,這大概是 the Chinese mainland 的叫法,這裡叫 Full doctoral proprosal presentation. 以前是交約10000字的文字檔給一個委員會審核(有些學系仍是這樣),近年則改為提交約1000字的短文給委員會審核,並公開作口頭報告20分鐘,然後被質詢10分鐘。所謂答辯,其實也是一種形式,因為經委員會核准的,就已經通過,口頭報告及質詢只是例行公事。話雖如此,面對一群對你的研究範圍認識不多的師生交代自己的研究,也有壓力。

昨天是兩位研究翻譯的內地學生,英文流利,不用看講稿,表達力在我之上。她們說的我不懂,其他師生所問的似乎也很客氣,沒有窮追猛打的情況。之後,跟幾位內地同學略作交談,有兩位來自廣州,講了幾句久已沒機會說的廣東話。

(2026.2.1補:今天聽另一位已移民紐絲綸的學生報告,她年輕美麗,英語流利,題目跟上潮流,前途無可限量。導師說她在內地名校畢業,在另一城市也有好工作,卻又跑來這裡,有點大惑不解。她補充一句,她研究的不是我們研究的老學究的東西,然後彼此大笑。)

最近幾次聽的報告,都有談到 AI 對翻譯的影響,AI 已是一個不能逃避的議題。其實,我也每天在用:

1. 學習語文

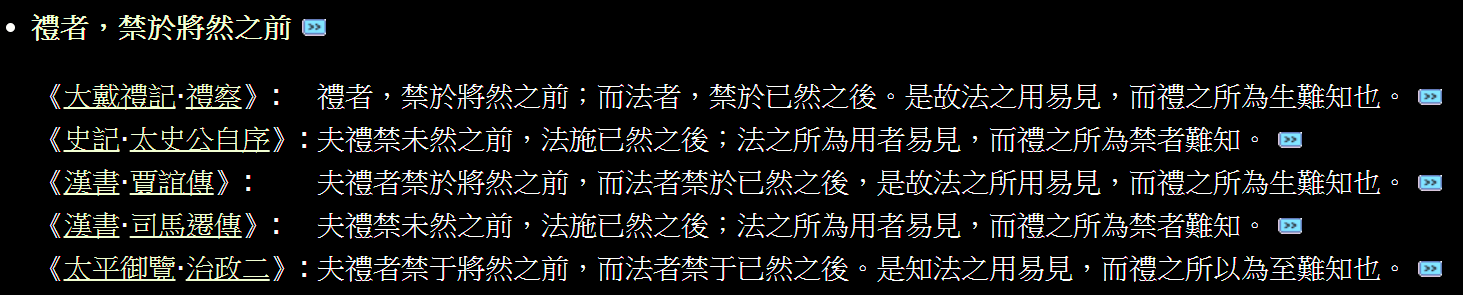

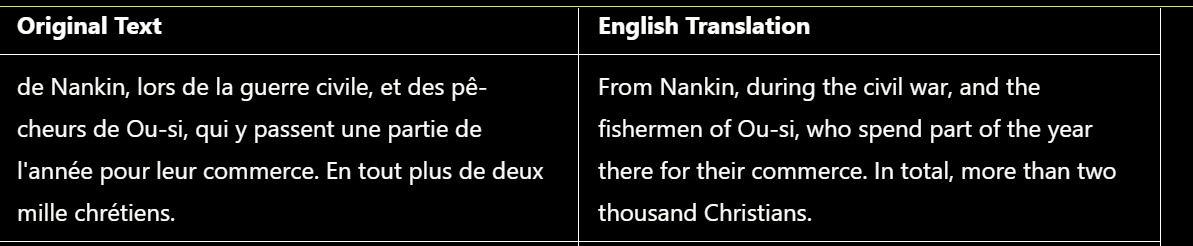

我會叫它把書本一頁的文字認出來,放在表格左邊,然後翻譯成英文,放在右邊。不同的語文我指明方向,或是在長的元音加註、或是transliterate。

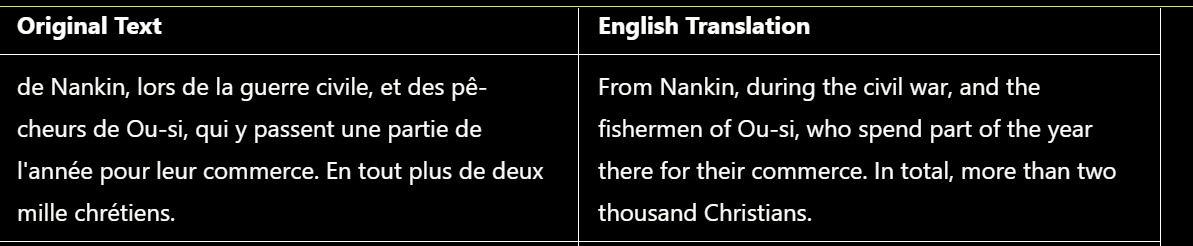

我用的 monica 有個不錯的設計,可以高亮一個字或一段,並完成指定任務,例如度身訂做字典、翻譯、語法說明等等,不必跳到另一版面操作,方便快手,也實在可以學到東西。

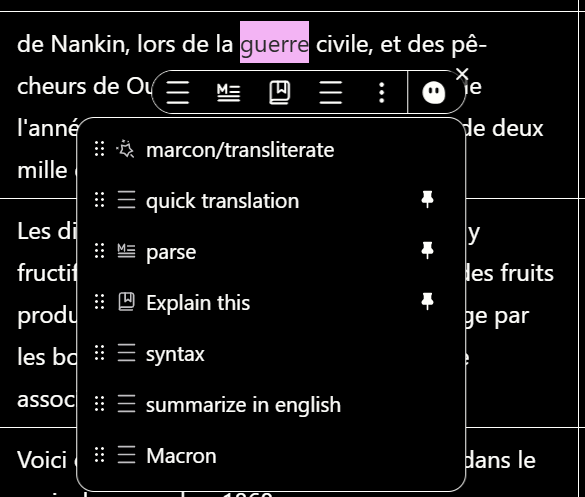

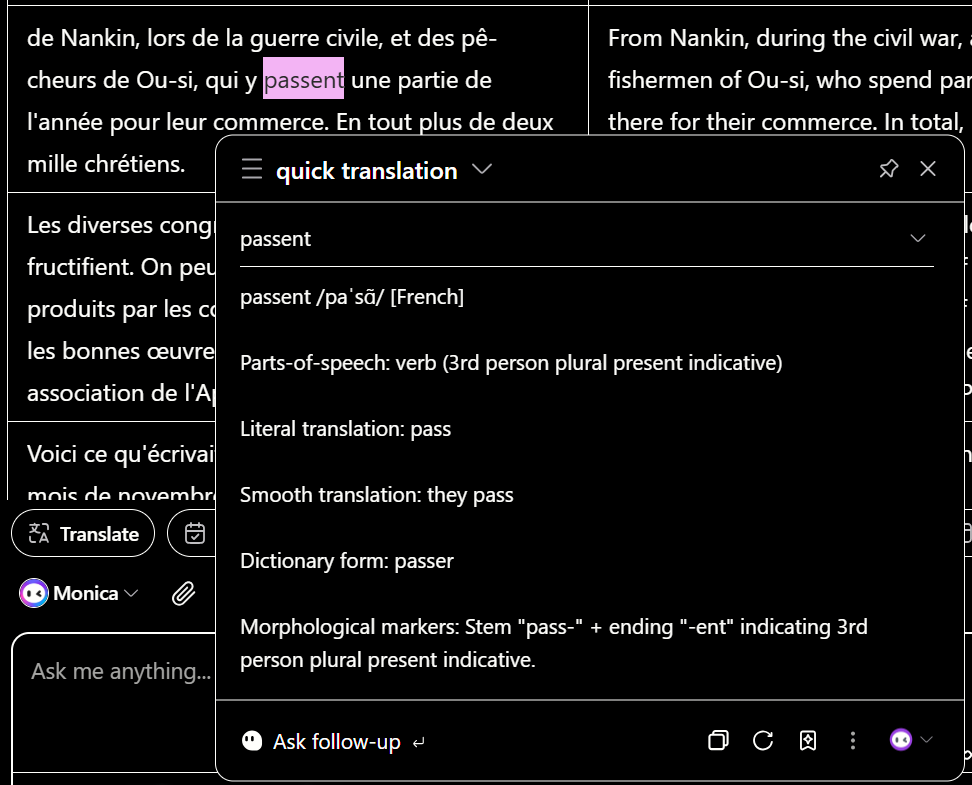

雖然我知道 AI 不是百分百可靠,例如下圖 passent 的發音是 ” /pɑːs/”,它錯了。但它實在超級快手,如果我逐字查字典,也不保證準確,分分鐘根本查不出來。所以,我覺得已可收貨。

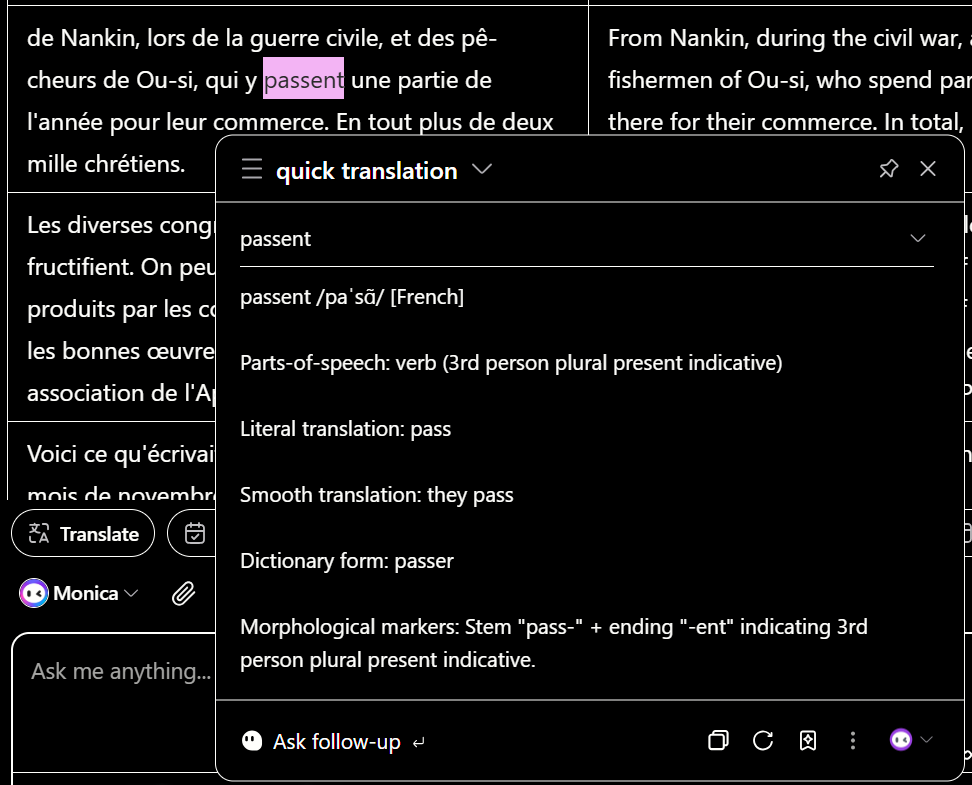

我最近讀完了史式徽的江南傳教史法文版,前後讀了兩年多;現在開始讀另一本記 1868年 江南傳教區的法文書,具體操作如下圖:

2. 整理資料

我會利用不同的 prompt 來處理資料,例如叫它用列點方式抽取文章重點,或者用學術論文的方式重整文章(即按研究問題、理論、方法、文獻綜述等格局分析文章)。

至於YouTube的學術討論,我會先把 YouTube 的連結傳到 https://notegpt.io/youtube-transcript-generator ,化語言為文字,再用 AI 來綜合整理討論者的立場、觀點異同、證據等。這樣,那些開場白、插科打諢的廢話、反來覆去人肉錄音機類的無效發言等可以完全抹掉,只保留在實質內容的東西,而且更具條理,更能突顯講者如何針鋒相對。

AI 懂得討好人,你問它問題,它總會說你問得好,然後才回答。古人云:“獨學而無友,則孤陋而寡聞” (《禮記·學記》) 我認為在新時代,真的可以獨學而又不會孤陋而寡聞。只不過,在真偽難辨的年代,更要保持批判精神、敢於質疑、善於質疑,要選相對可靠的 AI ,比較不同的 AI,才不會被上當。中國香港不能直接用 ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, 已自斷幾臂,不過祖國有 DeepSeek,公開透明、免費使用。中國香港市民可以用由中國香港自行研發的[中國]港話通,安全、免費,每次查詢只需耐心等待 30 秒後會有回覆,並會自行糾錯,把政治不正確的字句改換,我擁抱熱愛支持感動謝恩尊敬崇拜讚嘆膜拜歌頌感激涕零五體投地頂禮膜拜萬分景仰無限崇敬深深折服。[這句熱情澎湃,充滿正能量,我沒有能力寫出來,由 AI 代勞。]